MingusMag | Title 587 | NotTitle 588

© Copyright 2003 © Copyright 2003 |

" It is the mark of an educated mind to be able to entertain a thought without accepting it." Aristotle

Editors Note: There is no Mingus Mag nore Nag I am just enjoying the synchronicity of the WWW and that hypocrisy stuff. WE invented Germ warfare. Small Pox.Anthrax ... Coff coff!

|

MingusMag For your attention Date: Sat, 14 Jun 2003 23:40:47 +0000 (UTC)

click this> For a treet from my fortunecity Archive

Drawing by Judith Wolfe RHONDA BARTLE Making People

____________________________________________

tech stuff http://www.sr-71.org/groomlake/index.htm

________________________________________________________________

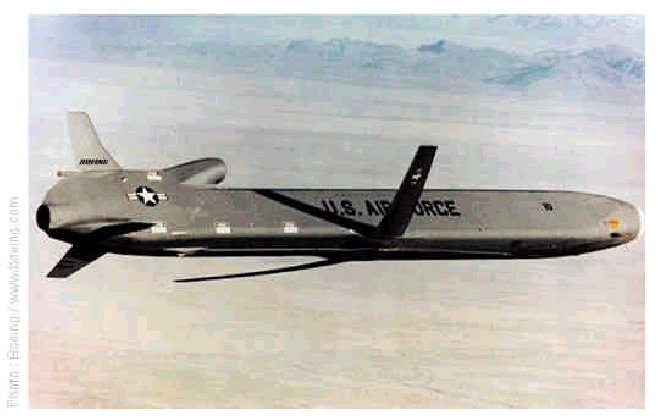

About Robert C. Michelson's Drone Project

|

Editors note: Please don't be fooled by the double speak creating felicitous false impression "WE" are part of a huge modern civilization, the fact remains that 8 out of 10 human beings on the earth don't know what a phone is and subsist on less than $1.00 a day (starvation unto death while we watch it or some thing like it or about it or for it on TV ) and are generally too programmed brainwashed to draw personal conclusion that it is time to act in, if not sympathy in harmony, politically , morally, transpersonal or other wise religiously within an empathy code of true self interest in his/her own image. Be aware there is No New World Order! Would that there were any institution claiming that this world as it is really was its handy work what it wanted "life to be " a credit most often given to a Deity called various names like god and were that entity an actual sentient being one must assume it was bereft of all senses save cruelty and sadistic irony states of consciousness which are generally toxic to most humans and rarely sustainable for a prolonged period of time.

|

____________________________________________________

THE SECOND CRACK IN THAT COSMIC EGG OF RACISM

Well It looks like NYC got the Message

Rense.com

"Miracle"At A Wisconsin High School

StratiaWire.com11-1-2

APPLETON, Wisconsin -- A revolution has occurred. It's taken place in the Central Alternative High School. The kids now behave. The hallways aren't frantic. Even the teachers are happy.

The school used to be out of control. Kids packed weapons. Discipline problems swamped the principal's office.

But not since 1997.

What happened? Did they line every inch of space with cops? Did they spray valium gas in the classrooms? Did they install metal detectors in the bathrooms? Did they build holding cells in the gym?

Afraid not. In 1997, a private group called Natural Ovens began installing a healthy lunch program. Huh?

Fast-food burgers, fries, and burritos gave way to fresh salads, meats "preparedwith old-fashioned recipes," and whole grain bread. Fresh fruits were added to the menu.

Good drinking water arrived.

Vending machines were removed.

As reported in a newsletter called Pure Facts, "Grades are up, truancy is no longer a problem, arguments are rare, and teachers are able to spend their time teaching."

Principal LuAnn Coenen, who files annual reports with the state of Wisconsin, has turned in some staggering figures since 1997. Drop-outs? Students expelled? Students discovered to be using drugs? Carrying weapons? Committing suicide? Every category has come up ZERO. Every year.

Mary Bruyette, a teacher, states, "I don't have to deal with daily discipline issuesI don't have disruptions in class or the difficulties with student behavior I experienced before we started the food program."

One student asserted, "Now that I can concentrate I think it's easier to get along with people" What a concept---eating healthier food increases concentration.

Principal Coenen sums it up: "I can't buy the argument that it's too costly for schools to provide good nutrition for their students. I found that one cost will reduce another. I don't have the vandalism. I don't have the litter. I don't have the need for high security."

At a nearby middle school, the new food program is catching on. A teacher there, Dennis Abram, reports, "I've taught here almost 30 years. I see the kids this year as calmer, easier to talk to. They just seem more rational. I had thought about retiring this year and basically I've decided to teach another year---I'm having too much fun!"

Pure Facts, the newsletter that ran this story, is published by a non-profit organization called The Feingold Association, which has existed since 1976.

Part of its mission is to "generate public awareness of the potential role of foods and synthetic additives in behavior, learning and health problems. The [Feingold] program is based on a diet eliminating synthetic colors, synthetic flavors, and the preservatives BHA, BHT, and TBHQ."

Thirty years ago there was a Dr. Feingold. His breakthrough work proved the connection between these negative factors in food and the lives of children.

Hailed as a revolutionary advance, Feingold's findings were soon trashed by the medical cartel, since those findings threatened the drugs-for-everything,disease-model concept

of modern healthcare.

But Feingold's followers have kept his work alive.

If what happened in Appleton, Wisconsin, takes hold in many other communities across America, perhaps the ravenous corporations who invade school space with their vending machines and junk food will be tossed out on their behinds.

It could happen.

And perhaps ADHD will become a dinosaur. A non-disease that was once attributed to errant brain chemistry. And perhaps Ritalin will be seen as just another toxic chemical that was added to the bodies of kids in a crazed attempt to put a lid on behavior that, in part, was the result of a subversion of the food supply.

For those readers who ask me about solutions to the problems we face---here is a real solution. Help these groups. Get involved. Step into the fray. Stand up and be counted.

The drug companies aren't going to do it. They're busy estimating the size of their potential markets. They're building their chemical pipelines into the minds and bodies of the young.

Every great revolution starts with a foothold. Sounds like Natural Ovens andThe Feingold Association have made strong cuts into the big rock of ignorance and greed.

First published 10-14-2000

Miracle At A Wisconsin High School http://www.rense.com/general31/miracle.htm

.MainPage http://www.rense.com

Miracle At A Wisconsin High School

|

Thanx 2 cton who spotted this on the Guardian Unlimited

Note from cton 4 : mingusmagazine.com -------To see this story with its related links on the

Guardian Unlimited site, go to http://www.guardian.co.uk

Fast forward into trouble Four years ago, Bhutan, the fabled Himalayan Shangri-la, became

the last nation on earth to introduce television. Suddenly a culture, barely changed in centuries,

was bombarded by 46 cable channels. And all too soon came Bhutan's first crime wave -

murder, fraud, drug offences.

Cathy Scott-Clark and Adrian Levy report from a country crash-landing in the 21st century

Thursday June 12 2003 The Guardian

April 2002 was a turbulent month for the people of Bhutan. One of the remotest nations in the

world, perched high in the snowlines of the Himalayas, suffered a crime wave. The 700,000

inhabitants of a kingdom that calls itself the Land of the Thunder Dragon had never experienced

serious law-breaking before. Yet now there were reports from many towns and villages of fraud,

violence and even murder.

The Bhutanese had always been proud of their incorruptible officials - until Parop Tshering,

the 42-year-old chief accountant of the State Trading Corporation, was charged on April 5 with

embezzling 4.5m ngultrums (£70,000). Every aspect of Bhutanese life is steeped in

Himalayan Buddhism, and yet on April 13 the Royal Bhutan police began searching the provincial

town of Mongar for thieves who had vandalised and robbed three of the country's most ancient

stupas. Three days later in Thimphu, Bhutan's sedate capital, where overindulgence in rice wine

had been the only social vice, Dorje, a 37-year-old truck driver, bludgeoned his wife to death

after she discovered he was addicted to heroin. In Bhutan, family welfare has always come

first; then, on April 28, Sonam, a 42-year-old farmer, drove his terrified in-laws off a cliff

in a drunken rage, killing his niece and injuring his sister.

Why was this kingdom with its head in the clouds falling victim to the kind of crime associated

with urban life in America and Europe? For the Bhutanese, the only explanation seemed to be

five large satellite dishes, planted in a vegetable patch, ringed by sugar-pink cosmos flowers

on the outskirts of Thimphu.

In June 1999, Bhutan became the last nation in the world to turn on television. The Dragon King

had lifted a ban on the small screen as part of a radical plan to modernise his country, and

those who could afford the £4-a-month subscription signed up in their thousands to a cable

service that provided 46 channels of round-the-clock entertainment, much of it from Rupert

Murdoch's Star TV network.

Four years on, those same subscribers are beginning to accuse television of smothering their

unique culture, of promoting a world that is incompatible with their own, and of threatening to

destroy an idyll where time has stood still for half a millennium.

A refugee monk from Tibet, the Shabdrung, created this tiny country in 1616 as a bey-yul, or

Buddhist sanctuary, a refuge from the ills of the world. So successful were he and his

descendants at isolating themselves that by the 1930s virtually all that was known of Bhutan in

the west was James Hilton's novel, Lost Horizon. He called it Shangri-la, a secret Himalayan

valley, whose people never grew old and lived by principles laid down by their high lama: "Here

we shall stay with our books and our music and our meditations, conserving the frail elegancies

of a dying age."

In the real Bhutan, there were no public hospitals or schools until the 1950s, and no paper

currency, roads or electricity until several years after that. Bhutan had no diplomatic

relations with any other country until 1961, and the first invited western visitors came only

in 1974, for the coronation of the current monarch: Dragon King Jigme Singye Wangchuck. Today,

although a constant stream of people are moving to Thimphu - with their cars - there is still

no word in dzongkha, the Bhutanese language, for traffic jam.

But none of these developments, it seems, has made such a fundamental impact on Bhutanese life

as TV. Since the April 2002 crime wave, the national newspaper, Kuensel, has called for the

censoring of television (some have even suggested that foreign broadcasters, such as Star TV,

be banned altogether). An editorial warns: "We are seeing for the first time broken families,

school dropouts and other negative youth crimes. We are beginning to see crime associated with

drug users all over the world - shoplifting, burglary and violence."

Every week, the letters page carries columns of worried correspondence: "Dear Editor, TV is

very bad for our country... it controls our minds... and makes [us] crazy. The enemy is right

here with us in our own living room. People behave like the actors, and are now anxious, greedy

and discontent."

But is television really destroying this last refuge for Himalayan Buddhism, the preserve of

tens of thousands of ancient books and a lifestyle that China has already obliterated over the

border in Tibet? Can TV reasonably be accused of weakening spiritual values, of inciting fraud

and murder among a peaceable people? Or is Bhutan's new anti-TV lobby just a cover for those in

fear of change?

Television always gets the blame in the west when society undergoes convulsions, and there are

always those ready with a counter argument. In Bhutan, thanks to its political and geographic

isolation, and the abruptness with which its people embraced those 46 cable channels, the issue

should be more clearcut. And for those of us sitting on the couch in the west, how the kingdom

is affected by TV may well help to find an answer to the question that has evaded us: have we

become the product of what we watch?

The Bhutanese government itself says that it is too early to decide. Only Sangay Ngedup,

minister for health and education, will concede that there is a gulf opening up between old

Bhutan and the new: "Until recently, we shied away from killing insects, and yet now we

Bhutanese are asked to watch people on TV blowing heads off with shotguns. Will we now be

blowing each other's heads off?"

Arriving at dusk, we pass medieval fortresses and pressed-mud towers, their roofs carpeted with

drying scarlet chillies. Faint beads of electric light outline sleepy Thimphu. Twisting lanes

rise and fall along the hillside, all of them leading to the central clock tower, where the

battered corpse of Tshering, a 50-year-old farmer, was found. In this Brueghel-like scene,

crowded and shambolic, where the entire population shares fewer than two dozen names, TV is

omnipresent. Potato stores sell flat-screen Trinitrons; old penitents whirl their prayer wheels

outside the Sony service centre; inside every candle-lit shop-house a brand new screen

flickers.

His Excellency Jigmi Thinley, Bhutan's foreign minister, greets us wrapped in an orange scarf,

a foot-long silver sword hanging over his ceremonial robe, or gho. He sweeps us into a pillared

hall embossed with golden dragons to explain why the king welcomed cable television to the Land

of the Thunder Dragon. "We wanted a goal different from the material concept of maximising

gross national product pursued by western governments," he says with a beatific smile. "His

Majesty decided that, as a spiritual society, happiness was the most important thing for us -

something that had never been discussed before as a policy goal or pronounced as the

responsibility of the state." And so, in 1998, the Dragon King defined his nation's guiding

principle as Gross National Happiness.

But happiness proved to be an elusive concept. The Bhutanese wondered whether it increased with

a bigger house or the number of revolutions of a prayer wheel. A delegation from the foreign

ministry was sent abroad to investigate whether happiness could be measured. They finally found

a Dutch professor who had made its study his life's work and were disappointed to learn that

his conclusion was that happiness equalled £6,400 a year - the minimum on which one could

live comfortably. It was a bald and irrelevant answer for the Bhutanese middle classes, whose

average annual salary was barely £1,000 and whose outlook was slightly more metaphysical.

The people of Bhutan, however, finally decided for themselves what would make them happy.

France 1998 was driving the football-mad kingdom into a frenzy of goggle-eyed envy of those who

were able to watch the World Cup on television. The small screen had always been prohibited in

Bhutan, although the kingdom was crisscrossed by satellite signals that it was finding

increasingly difficult to keep out. Even the king was rumoured to have a Star TV satellite

package installed at his palace. Faced by recriminations, the government relented and Bhutan's

Olympic Committee was permitted to erect a giant screen in Changlimithang stadium - but only

temporarily.

A TV screen in the middle of Thimphu was a revolutionary sight. The kingdom, for so long an

autocracy, had only recently forged links with the outside world. In 1959, China quelled an

uprising in Tibet, spilling war into the north of Bhutan, forcing the previous Dragon King to

forge diplomatic ties for the first time in the country's history. "Even then," says the

foreign minister, "we were determined not to become pawns on a chessboard and decided not to

have formal relations with the superpowers. We also sensed the regret of many nations across

the world at what they had lost in terms of values and culture."

The current Dragon King's father initiated a careful programme of modernisation that saw his

people embrace the kind of material progress that most western countries take centuries to

achieve: education, modern medicine, transportation, currency, electricity. However, mindful of

those afraid that foreign influences could destroy Bhutanese culture, he attempted to inhibit

conspicuous consumption. No Coca-Cola. No advertising hoardings. And definitely no television.

By France 1998, Bhutan had a new Dragon King and, under growing pressure from an unsettled

country, he had a new political agenda. That year, King Jigme Singye Wangchuck announced he

would give up his role as head of government and cede power to the national assembly. The

people would be consulted about the drafting of a constitution. The process would complete

Bhutan's transformation from monarchist Shangri-la into a modern democracy. And television

would play its part.

The prime minister of Bhutan, Kinzang Dorji, has invited us to tea and we sit with him

beneath a large thangka painting of the Wheel of Life. "His Majesty wants the Bhutanese

people to run their own country. But many are frightened of the responsibility. A lot of

things have changed very quickly in Bhutan, and we do recognise that some people

feel lost, at sea," the prime minister explains. "Watching news on the BBC and CNN

enables them to see how democracies work in other parts of the world, how people can

take charge of their own destinies. The old feudal ways have to end."

The year after France beat Brazil 3-0 in the World Cup final, the people of Thimphu gathered

once again in Changlimithang stadium, this time to celebrate the Dragon King's silver jubilee.

On June 2 1999, he stood before them to announce that now they could watch TV whenever they

wanted. "But not everything you will see will be good," he warned. "It is my sincere hope that

the introduction of television will be beneficial to our people and country."

The prime minister insists that the introduction of television was carefully prepared: "To

mitigate the impact of negative messages, we launched firstly the Bhutan Broadcasting Service

[BBS] to provide a local educational and cultural service." Only after the BBS had

found its voice would a limited number of foreign channels be permitted to beam programmes into

Bhutan via local cable operators.

News footage from the first BBS broadcast of June 2 1999, records the cheer that resounded

around Changlimithang. Bhutan's spiritual and cultural leaders were all agreed that TV could

only increase the country's Gross National Happiness and help the people to pave the way to a

modern, democratic nation. Mynak Tulku, the reincarnation of a powerful lama, is the Dragon

King's unofficial ambassador for new technology. Light pouring in through the carved wooden

windows catches his large protruding ears and bathes the monk in a golden glow. Nearby, in the

main library, some of the oldest surviving texts in Tibetan Buddhism, dharmic verses penned in

liquid gold, are being digitised. "I am so excited about technology," beams the Tulku, the

epitome of the king's notion of Gross National Happiness. "And let me tell you that TV's OK, as

long as you appreciate that it is a transitory experience. I tell my students that it's like

rushing in from the cold, going straight to the heater and ending up with frostbite. Ha, ha. TV

can make you think that you are being educated, when in fact all you're doing is blinking your

life away with a remote control. Ha, ha."

The Bhutan Broadcasting Service was intended to be a bulwark against cable television. When we

call by, it is clear the studio is still not finished: the team of technicians hired from

Bollywood has gone home for Diwali. The state broadcaster has only one clip-on microphone, but

the features producer cannot find it. There are a bundle of programmes "in the can", he says,

but none is ready for broadcast. A list of feature ideas hangs on a board, each one eclipsed by

a large question mark: Bhutanese MTV? Candid Camera? Pop Idol? Big Brother?

There is no one else on any of the three floors of the BBS building, but there is a distant

clamour coming from outside. There, behind a garden shed, we eventually find the BBS cameramen

and reporters dressed in their billowing ghos, throwing giant darts at a clay target. It is a

badly needed team-building exercise, says Kinga Singye, the BBS executive director, with a

doleful voice that makes him sound as if he has had enough of the royal experiment in

television. He describes how, in 1999, the last people to learn of the lifting of the

television ban were those then charged with setting up the new national station. "They were

given three months to make it work. It was done with incredible haste - to be ready in time for

the king'ssilver jubilee. What the government wanted was hugely ambitious and expensive, yet we

didn't have experience and they had no funding to give," he says. Everyone was surprised when

the ministers then issued licences to cable TV operators in August 1999, a bare three months

after BBS went on air.

Three years later, in the absence of investment, BBS can still be transmitted only in Thimphu;

tapes of its shows bound for the remote eastern town of Trashigang take three days to arrive,

by bus and mule. "Our job was supposed to be to show people that not everything coming from

outside is good," Kinga Singye says. "But we are now being drowned out by the foreign TV

signals. People are continually disappointed in us." That evening, the nightly BBS News At

Seven begins at 7.10pm. A documentary on a Bhutanese football prodigy is mysteriously canned

halfway through. It is followed by some footage of an important government event, the Move For

Health. The sound is indistinct, the picture faded, the message lost.

Downtown, at the southern end of Norzin Lam high street, a wriggling crowd of children press

their faces to a shop window. Inside the headquarters of Sigma Cable, the walls are papered

with an X-Files calendar and posters for an HBO show called Hollywood Beauties. Beneath a

portrait of the Dragon King, the in-store TV shows wrestling before BeastMaster comes on. A man

in tigerskin trunks has trained his marmosets to infiltrate the palace of a barbarian king.

When the monarch is decapitated and gore slip-slaps across the screen, the children watching

outside screech with glee. Inside the Sigma office, the staff are scrapping over the remote

control, channel-hopping, mixing messages. President Bush in a 10-gallon hat welcomes Jiang

Zemin to Texas. Midgets wrestle on Star World. Female skaters catfight on Rollerball.

Today, Sigma Cable, whose feed comes from five large satellite dishes at the edge of the city,

is the most successful of more than 30 cable operators. Together, they supply virtually the

entire country, ensuring that even the folks in remote Trashigang can sit down every night to

watch Larry King Live.

Rinzy Dorje, Sigma's chief executive, wears a traditional gho but his mind is on fibreoptics

and broadband. He was one of the first people in Bhutan to learn to program a computer, and

back then (the 1980s) his machine came housed in a home-made wooden box. When he launched

Sigma on September 10 1999, he captured the market in Thimphu, signing up the queen mother,

the king and his four wives, among others. Between calls on his new mobile telephone, he defends

cable TV: "Look, Bhutan couldn't hold back any longer - we can't pretend we're still a medieval,

hermit nation. When the government finally got around to announcing cable TV, I was ready,

that's all. All the information you need to know on cable technology is on the net. I got

prices and sourced the parts in Delhi and Taiwan. And cable came to Bhutan. It's no big deal."

A disgruntled subscriber rings to complain that MTV has gone down. Are there are too many

channels? "I couldn't cut back on the channels even if I wanted to - the customers would go

elsewhere and Star TV wants us to show more channels, not fewer."

Have Bhutan's values been corroded by TV? "We are entitled to watch what we want, when we

want, if we want. And we are quite capable of weeding out the rubbish; turning off the crap," he

retorts.

However you look at it, it's obvious that the BBS has been charged down by the juggernaut of

Star TV. "If the government wanted to control what people watched, they should have legislated,

not tried to compete," says Rinzy Dorje.

It takes three days to pin down Leki Dorji, the deputy minister of communications, an

overloaded crown appointee who is also responsible for roads, urban renewal, civil aviation and

construction. He readily admits that, in its haste to introduce TV, the government failed to

prepare legislation. There is no film classification board or TV watershed in force here, no

regulations about media ownership. Companies such as Star TV are free to broadcast whatever

they want. Only three years after the introduction of cable did the government announce that a

media act would be drafted. Leki Dorji says his ministry is also planning an impact study, but

adds that he does not believe cable television is responsible for April's crime wave. "Yes, we

are seeing some different types of crime, but that just reflects the fact that our society is

changing in many ways. A culture as rich and sophisticated as ours can survive trash on TV and

people are quite capable of turning off the rubbish."

Whether the truck-driver Dorje was influenced by something he had watched on television when he

began smoking heroin or when he clubbed his wife to death has yet to be established. We will

not know whether the death of Sonam's niece had anything to do with the impatient, selfish

society promoted by television until the impact study is completed. But there is a wealth of

evidence that points to television having been a critical factor.

The marijuana that flourishes like a weed in every Bhutanese hedgerow was only ever used to

feed pigs before the advent of TV, but police have arrested hundreds for smoking it in recent

years. Six employees of the Bank of Bhutan have been sentenced for siphoning off 2.4m ngultrums

(£40,000). Six weeks before we arrived, 18 people were jailed after a gang of drunken boys

broke into houses to steal foreign currency and a 21-inch television set. During the holy

Bishwa Karma Puja celebrations, a man was stabbed in the stomach in a fight over alcohol. A

middle-class Thimphu boy is serving a sentence after putting on a bandanna and shooting up the

ceiling of a local bar with his dad's new gun. Police can barely control the fights at the new

hip-hop night on Saturdays.

While the government delays, an independent group of Bhutanese academics has carried out its

own impact study and found that cable television has caused "dramatic changes" to society,

being responsible for increasing crime, corruption, an uncontrolled desire for western

products, and changing attitudes to love and relationships. Dorji Penjore, one of the

researchers involved in the study, says: "Even my children are changing. They are fighting in

the playground, imitating techniques they see on World Wrestling Federation. Some have already

been injured, as they do not understand that what they see is not real. When I was growing up,

WWF meant World Wide Fund for Nature."

Kinley Dorji, editor of Kuensel (motto: That The Nation Shall Be Informed), warns that Bhutan's

ruling elite is out of touch. "We pride ourselves in being academic and sophisticated, but we

are also a very naive kingdom that does not yet fully understand the outside world. The

government underestimated how aggressively channels like Star market themselves, how little

they seem to care about programming, how virulent the message of the advertisers is." Kinley

Dorji, a member of the taskforce charged with drafting the kingdom's first media act, believes

Bhutanese society is in danger of being polarised by TV. "My generation, the ministers, lamas

and headteachers, have our grounding in old Bhutan and can apply ancient culture to this new

phenomenon. But the ordinary people, the villagers, are confused about whether they should be

ancient or modern, and the younger generation don't really care. They jettison traditional

culture for whatever they are sold on TV. Go and see real Bhutan, see how the people are

affected."

A fanfare of Tibetan trumpets booms through the pine forest. A rough choir of a thousand voices

sings out: "Move for, move for health." It is so early in the morning that the birds are still

asleep. But Sangay Ngedup, minister for health and education, has been on the path for hours.

His gho is bunched beneath his backpack, and a badge with the king's smiling face is pinned on

to his baseball hat. In the past 15 days, he has climbed and scrambled over some of the world's

most extreme terrain, from sea level to a rarefied 13,500ft in the Bhutanese Himalayas. Is

there anywhere else in the world where a cabinet minister would trek 560km to warn people

against becoming a nation of couch potatoes? "We used to think nothing of walking three days to

see our in-laws," he says. "Now we can't even be bothered to walk to the end of Norzin Lam high

street."

He pauses at an impromptu feeding station, gulping down salt tea and buttered yak's cheese.

"You can never predict the impact of things like TV or the urbanisation it brings with it," he

says. "But you can prepare. If the BBS was intended as our answer to the cable world, I have to

say that, at the moment, it is rather pathetic." Sangay Ngedup is one of the only government

ministers willing to voice concerns about television.

For the first time, he says, children are confiding in their teachers of feeling manic, envious

and stressed. Boys have been caught mugging for cash. A girl was discovered prostituting

herself for pocket money in a hotel in the southern town of Phuents-holing. "We have had to

send teachers to Canada to be trained as professional counsellors," says Sangay Ngedup. This

march is not just against a sedentary lifestyle; it is a protest against the values of the

cable channels. One child's placard proclaims, "Use dope, no hope." "Breast is best," a girl

shouts. "Enjoy the gift of sex with condoms," reads a toddler's T-shirt.

The next day, as they do every day at Yangchenphug high school, teachers prepare their pupils

for the nightly onslaught of foreign images on television. They pray to Jambayang, the Buddhist

god of wisdom, a recent addition to the school timetable insisted upon by the clergy. A class

of 15-year-olds are inquisitive and smart. How many of you have television, we ask. Laughter

fills the room. "We all have TV, sir and madam," a girl at the front pipes up.

"What's your culture like?" they ask. "Do you have universities? Does it rain a lot where you

come from?"

What do you like about TV, we ask the class. "Posh and Becks, Eminem, Linkin Park. We love The

Rock," they chorus. "Aliens. Homer Simpson." No mention of BBS. No one saw its documentary on

Buddhist festivals last night. Superficially, these pupils are as they would be in any school

in the world, but this is a country that has reached modernity at such breakneck speed that the

god of wisdom Jambayang is finding it virtually impossible to compete with the new icons.

A new section entitled "controversies" in the principal's annual report describes "marathon

staff meetings that continue on a war footing to discuss student discipline, substance abuse,

degradation of values in changing times". On another page is a short obituary for ninth-year

pupil Sonam Yoezer, "battered to death by an adult in the town". Violence, greed, pride,

jealousy, spite - some of the new subjects on the school curriculum, all of which teachers

attribute to the world of television. In his airy study, the principal, Karma Yeshey, whose MA

is from Leeds University but whose attitude is still otherworldly, pours Earl Grey tea. "Our

children live in two different worlds, one created by the school and another by cable. Our

challenge is to help them understand both, and we are terribly afraid of failing."

Outside Thimphu, the two worlds of Bhutan are already beginning to blur into one. In the heart

of the kingdom's spiritual capital of Punakha stands the Palace of Great Happiness, where the

Shabdrung, the country's founding father, is interred. Today a black wire crosses the

drawbridge to the 17th-century fortress, running through a top-floor casement and taking cable

television into the sacred shrine. So high is the demand for Oprah and Mutant X that in this

town the size of London's Blackheath there are now two rival operators vying for business.

The children of Punakha are, by the dozen, abandoning their ghos for jeans and T-shirts bearing

US wrestling logos; on their heads are Stars and Stripes bandannas. On the whitewashed mud wall

of the ancient crematorium, they have scrawled in charcoal a message in English: "Fuck off

Kinley and die."

How quickly their ancient culture is being supplanted by a mish-mash of alien ideas, while

their parents loiter for hours at a time in the Welcome Guest House, farmers with their new

socks embossed with Fila logos, all glued to David Beckham on Manchester United TV. A local

official tells us that in one village so many farmers were watching television that an entire

crop failed. It is not just a sedentary lifestyle this official is afraid of. Here, in the

Welcome Guest House, farmers' wives ogle adverts for a Mercedes that would cost more than a

lifetime's wages. Furniture "you've always desired", accessories "you have always wanted",

shoes "you've always dreamed of" - the messages from cable's sponsors come every five minutes,

and the audience watching them grows by the day.

There is something depressing about watching a society casting aside its unique character in

favour of a Californian beach. Cable TV has created, with acute speed, a nation of hungry

consumers from a kingdom that once acted collectively and spiritually.

Bhutan's isolation has made the impact of television all the clearer, even if the government

chooses to ignore it. Consider the results of the unofficial impact study. One third of girls

now want to look more American (whiter skin, blond hair). A similar proportion have new

approaches to relationships (boyfriends not husbands, sex not marriage). More than 35% of

parents prefer to watch TV than talk to their children. Almost 50% of the children watch for up

to 12 hours a day. Is this how we came to live in our Big Brother society, mesmerised by the

fate of minor celebrities fighting in the jungle?

Everyone is as yet too polite to say it, but, like all of us, the Dragon King underestimated

the power of TV, perceiving it as a benign and controllable force, allowing it free rein,

believing that his kingdom's culture was strong enough to resist its messages. But television

is a portal, and in Bhutan it is systematically replacing one culture with another, skewing the

notion of Gross National Happiness, persuading a nation of novice Buddhist consumers to

become preoccupied with themselves, rather than searching for their self.

Copyright Guardian Newspapers Limited

Caution!! endless rant alert!

_________________________________________________________________

Hi C

"Whoz the Nigger now?" It's your culture

You eat it, or you bought it YOU wear it."

So what ever the Sultan of Bluenose or Bhutan wherever whatever clear headed enough

to resist the bleach blond suck dry scam was Right to want to keep the CIA MAFIA AND

HOLLYWOOD OUT All these years what else is new... They should build a Casino or

better yet franchise there own TV show from “The Palace or Temple” with a bunch of those

teen X virgin Cuchies in plastic wigs lap dancing like in Hong Kong and Bang Cock New

Jersey Girls Gong! Wild with Snoop Bozo Bo.

Don’t just do nothing sit there You just think you think, and do nothing but think you think, and do

so little and rightly hardly speaking in a true voice loudly whispering surging approaching the

world like it owns you whenever you speak its about the failures of others to gratify you like a 5

year old that can do nothing but whine like a 3 or 3 year old because you like all of us are waiting

for someone to do it for you or with you "I am looking for the late night Video Wild gone wild "

especially the chimps in the bush not because it is some how sexy to the contrary it puts the maximum

consumer cool on liquid Nitrogen to see what the geno type only 1.100% not human are doing daily with

out the "nicety of speaking English" ( how will I know that you are lying to me , My lips will be moving")

just what we do only there are non partisan about it no Nute Gingrich sneakily working to "Help Blacks"

only to betray them totally in his final career and never be called a slut like baboons semi humping on the

belly of the one actually getting Porked and whacking off in the most annoying way as if to say yes I have

seen all of the cruelties of human kind and I am happy to be as crude and artificial as the next buffoon

baboon you will listen to that is going to tell you just what you want to believe there is a Santa Claus and

he doesn't eat Bambi, Hua?!! Take one look at all of the things on earth that represent human habitation

from the past what have we learned? ,It’s a farce It’s a comedy It’s a tragedy it’s amazing to see to be

but so what will happen when human beings can live in a house that they essentially never have to leave

because "it Works " It makes and takes care of ALL of its inhabitants food waist management and Global

communications as part of the family Birth Right Isn't that what every body wants autonomy less consumerism more time to be "alive" and all for the same price of a new car then add the cost of land & calculate the waist heat and we still probably wont make it to 2020 because of the Caesium 135 in the water of the Colorado River( because of those Stupendously Stupidcocksuckingracistassholeswhiteboys

trying to finish off the Indians over the last 50 years by dumping all of the leftover radio active waist in the

“INDIANS WATER” ignoring the fact that the Earth doesn’t Givaflyingfuck what your so called race is)

and WE! have the NUKE! and HIV and Slavery and more War so that fancy turtle shell that provides the

total needs package and needs only sun and water to support a family of what 1,2,3,4,5, 6,7, 8. 9,

10? So called People will still play like the Beverly-hillbillies & incest sueside, Hatfields & McCoy's,Waco,

Colimbine and whatever monkey see monkey do stunt that ...

Speaking of that did you see the Pop-Science Article about playing back recorded or live voices

so it feels like the voice is talking inside of your head? Try this scenario out for size” the voice is

in side your tells you " Head you only do peace work and are happy to eat only one soy cracker a

day and you don't mind drinking your own boiled urine because as if its a proper subject for a play

(so long as every body is white) well the filter is clogged up or down and at least you know its

yours and not some 6 foot tall featherless chicken a No Named Shaved Grizley Bare hybrid human mutant under house arrest next door, that some Australian Cloning company moved in to a vacant Domestic State apt. house next door to you to allow it to hang out with humans till it learns English. IT is part human the tiny chicken brain was removed and language skill section

of a human clone was added so it wouldn't make so much noise on the way to the Abitraw , meat packing houses this is little better than slaughter house because they don't get along very well with each otherletalone the fact that some bimbo modeled them after working class Brits Liverpool hooker district so the language is to say the least colorfull . Did I say 6 foot tall chicken? No eminent threat from rebellion it has a Union aproved Genome package and besides it has no hands and only eats Hybrid corn its a shame too it does a real neet Elvis Costello Kareyone impersination.

"total needs package and needs only sun and water to support a family of what "

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________

An examination of the threats to the Snake River Plain aquifere http://www.ieer.org/reports/poison/pvz.pdf

from the Idaho National Engineering and Environmental Laboratory.

_______________________________________________________________________________________________

|

I don't care who is doing this thing to chickens it is an abomination on the path to

the American shark farm cemetery x-Nazi technology or modern eugenics what's

next growing fur in the poor and homeless so they wont need to work and they

can keep warm under the bridges and in the abandoned buildings of old town until

we need to harvest there organs and mystery meat ... This Story isn't Mad Scientist

Hoax it's Government funded Research with no ethical guidelines and perhaps a

terminal type of gargantuan sadistic hubris, arrogance greed for profit and ironic

cruelty and a contempt for life considering...

IF YOU DON'T SEE THIS AS AN ABOMINATION ?

Although this paper was written in 1993, with the increasing momentum of the reparations movement it remains relevant. --TOPLAB Reparations and A New Global Order: A Comparative Overview by Professor Chinweizu

African Experience

Thanks Kim kimnora.com

Occult , covert and internecine are not the same thing.

Edward O. Wilson On Ants and Humans

is a well-known biologist and professor of entomology at Harvard University. His latest book, In Search of Nature, is published by

Allen Lane in the UK. articles

If Homo sapiens goes the way of the Dinosaur, we have

only ourselves to blame.

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

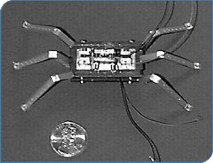

Fire Ant Ant Answer Man Mech. Ant An Answer?

The war with nature is important now more than ever. Digital dear ticks called "Viruses" Cost us time money and grief but there isn't any goofy geeky nurd that

I can garrote at the end of the rainbow, there may be more Vectors from Plumb Island than we think but the conspicuous squaller that is nature is flipping us the ultimate Bone. No mater what we intend good things can be turned into "Evil Things This Way Come." All we can do is guess what our best intentions will become. Micro cooties with cameras may help us kill very pesky critters but they can also make moot any concept that we call the right of privacy. ED.

Read This Book

A True Must Read!

|

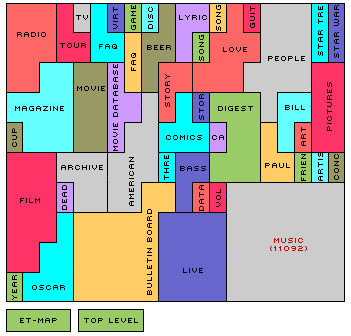

A Map of Yahoo! - Mappa.Mundi Magazine - Map of the Month

By Martin Dodge, CASA

|

ET-Map was created may

wish to consult the

research paper "Internet

The top-level of ET-Map,

created by a team led by Hsinchun Chen.

© National Science Foundation,

NOTused by permission.

|

This image is based on the ET-Map created by a team led by Hsinchun Chen. ? National Science Foundation,used by permission.

Copyright © 1999, 2000 media.org. ISSN: 1530-3314

|

This company is looking cool 4 Web Designer,

Content Management, Shopping Cart, and

eCommerce Hosting all around $100.00 with

a "free Trial!! http://www.theinternetsolution.com/

I Know my site sucks compared to this professional school look but I work alone and don't have to watch my back as much as in the Trotsky Stalin Era...How...Yeah right..

|

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

" It is the mark of an educated mind to be able to entertain a thought

without accepting it." Aristotle

ZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZ

More Quotations To Consider

At 56k its going to take a while so

Pick one of my favorite pages at this site right click and

open a new window while this one loads ED: <click this

In Motion Magazine

not launched still in bata

|

Visit NOIZART.COM

R@wman at 18

t e m p o r a l y r a n d o m l i n k s b e l o w

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

VERY Cool Links ED: searchlores.org searchlore.org

Web Searchlores Advanced Internet searching strategies & advices.

Updated 5 days ago http://www.searchlores.org/index.html

too little too late http://web.archive.org/web/ *

R mut:

The Mutt:

The R Mutt story a reasonably intereinteresting take for the kiddies...

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

An examination of the threats to the Snake River Plain aquifere http://www.ieer.org/reports/poison/pvz.pdf

from the Idaho National Engineering and Environmental Laboratory.

===========================================================

insight analysis, and commentary on the innovations and trends of contemporary computing, and on its growing number of related technologies. An ongoing journey towards understanding, & profiting from, a world of exponential technological growth!

All material on the Web site is copyright © 2001-2003, Jeffrey R. Harrow. All Rights Reserved.

===========================================================

R mutt

Little Orphan Annie, Lill Abner, Little Nemo

No exactly a pisseligant concept of the flying fence I had in mind, you can lead a whore to culture but you cant make her think.

|